At the end of the Seven Years’ War (called the French and Indian War in America), England emerged as the big winner. It had gained control of eastern North America, from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, and from Labrador to Louisiana.

This victory, sealed by the Treaty of Paris in 1763, came at a steep price. England’s national debt had swelled by an additional £59 million, equivalent to nearly £15 billion today. And the drain on the Treasury didn’t stop there. England had to deploy thousands of soldiers to keep the French and Spanish out and to keep the Indigenous population under control.

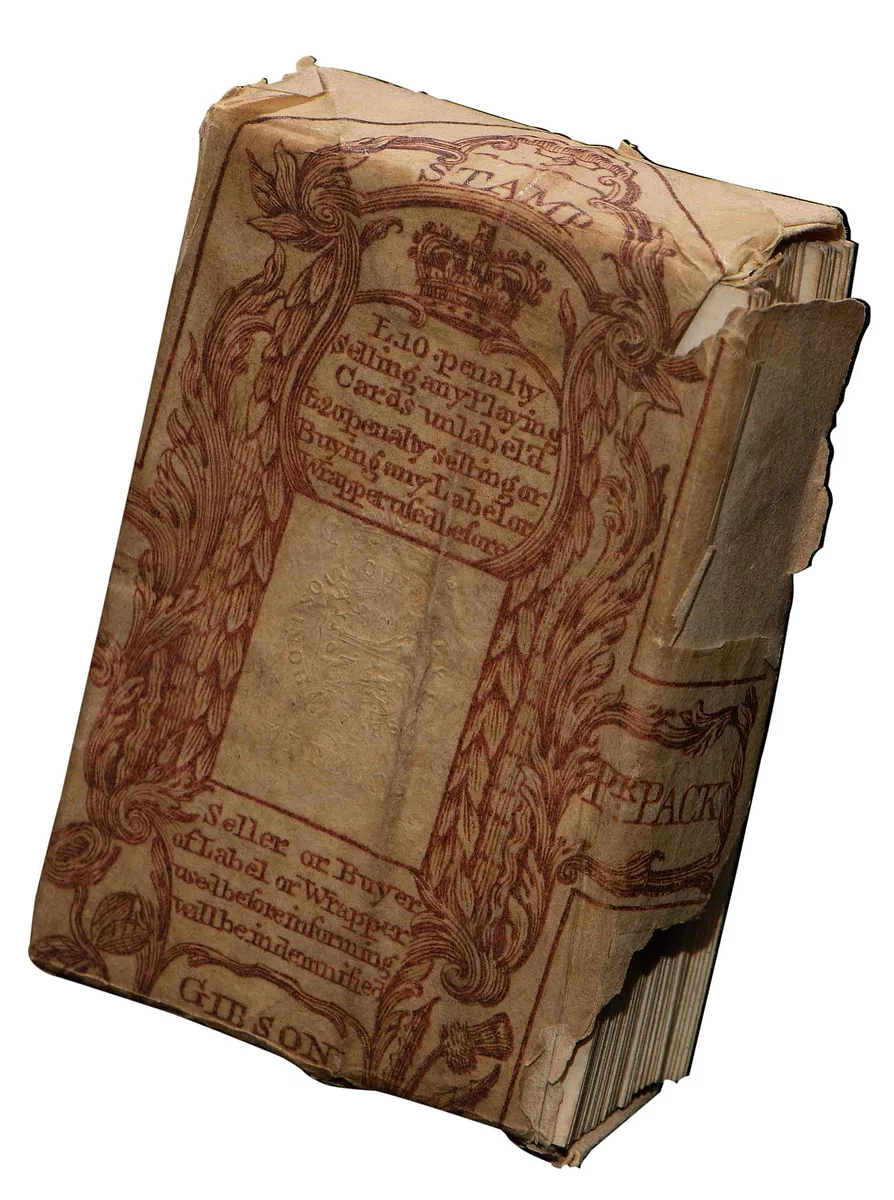

To the British Parliament, it made sense that their American colonies should pick up the tab; after all, they were the most vulnerable should any threat arise in the newly conquered territory. So, in 1765, they passed the Stamp Act, imposing a tax on a wide range of paper goods in the colonies: newspapers, legal documents, posters and pamphlets, playing cards, and, for good measure, dice. Without knowing it, they began a cascade of events that would trigger the American Revolution a decade later.

A view of the obelisk erected under the Liberty-Tree in Boston on the rejoicings for the repeal of the Stamp-Act by Paul Revere, 1766

Colonists had been accustomed—if not happy—to pay duties on trade goods imported from England, but the Stamp Act was different. It taxed items that originated in America, and this sparked outrage from the colonists, not only at the financial burden, but also at being subject to the will of legislators they didn’t elect. For over a century, England had allowed its American colonies a fair measure of self-government, and they bridled at taxation without representation.

Protests erupted throughout the colonies. In Boston, rioters ransacked the home of the city’s stamp official, Andrew Oliver, and hanged him in effigy. The Stamp Act proved unenforceable, and Parliament repealed it one year after it was passed.

The Boston Tea Party by an English artist. Americans throwing Cargoes of the Tea Ships into the River, at Boston by W.D. Cooper, 1789

The repeal of the Stamp Act was marked by spectacular public celebrations. On May 19, 1766, crowds filled Boston Common to see a ten-foot-tall, illuminated obelisk erected by the Sons of Liberty, decorated with allegorical images extolling liberty and condemning Parliament and the Stamp Act. The obelisk caught fire when the rally culminated in a display of fireworks, leaving only an engraving by Patriot Paul Revere to show us what it looked like.

The images on the obelisk reveal the mood in the colonies in 1766. The Stamp Act is represented by Satan himself, but above him appear pictures of individuals that the colonists considered their allies, including King George III. They remained loyal British subjects even as they resisted Parliament’s efforts to curtail their self-rule. That organized and very public resistance planted the idea of independence in the minds of the colonists.

But Parliament still needed money, so in 1767 they enacted the Townshend Acts, imposing taxes on goods including glass, paper, paint, and tea. Colonists responded by boycotting British imports. In 1768, England sent thousands of soldiers to Boston to keep protests under control. Tensions grew between civilians and the occupying troops, and in 1770, Redcoats killed five civilians in the incident we know as the Boston Massacre. It didn’t start a war, but it moved the colonies one step closer.

Townshend Act boycotts continued until Parliament repealed most of the taxes in 1770, but they kept the tax on tea, and that fueled further animosity. Although tea was expensive, almost everyone drank it, so the tax provoked anger across all strata of society. Protests escalated from boycotts to public tea-burnings and, finally, to the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773. As many as 150 men boarded ships to destroy the hated tea while sympathetic onlookers cheered from the shore.

Dramatic as it was, it remained a peaceful protest. The provincials took care to harm no one, and even more surprisingly, British officers watched the whole scene from the deck of a nearby warship but held their fire lest they injure the bystanders on shore.

England’s Prime Minister, Lord North, wasn’t so benign. “Boston had been the ringleader in all riots,” he fumed when informed of the Tea Party. “Therefore Boston ought to be the principal object of our attention for punishment.”1 Parliament’s first rebuke was to shut down the port of Boston, cutting off essential trade. But what really struck a nerve was the Massachusetts Government Act, passed in May 1774.

The act installed a military governor, General Thomas Gage, and replaced elected judges, sheriffs, marshals, and other officials with men appointed by Gage. Jurors would be chosen by the Governor’s handpicked sheriffs. All members of the Council, or upper house, of the Massachusetts legislature would be appointed by the Crown. Town meetings, the most vital channel for the voice of the people, were forbidden unless sanctioned by General Gage, who also had to approve the agendas in advance.

The people of Massachusetts saw themselves being subjected to a government that was no longer accountable to its citizens, a situation that would not change without direct and forceful action.

General Thomas Gage, portrait by John Singleton Copley, 1788.

In lieu of town meetings, provincials gathered informally in taverns or public squares. These clandestine assemblies soon evolved into a shadow government, the Committees of Correspondence, a network that enabled local leaders to share information and organize acts of resistance. A Salem judge, Peter Frye, tried to arrest citizens who met illegally, but the people of Essex County united to stop him by refusing to do business with him. Unable to buy so much as a sack of flour to feed his family, Frye resigned his post.

Such acts of resistance remained nonviolent even as they escalated in number and intensity. Although the British government denounced the activists as a mob, their protests were planned with care and executed with restraint. They sometimes destroyed personal property, but they rarely inflicted bodily harm.

The people refused to let the Crown-controlled courts operate. On August 16, 1774, Berkshire County court officials arrived to find the courthouse packed wall-to-wall with protestors. They simply couldn’t get into the building. Two weeks later, a crowd of over three thousand people thronged the Hampshire County courthouse, marching to fifes and drums, and forced the officers of the court to put their signatures on a pledge renouncing the Massachusetts Government Act.

In September 1774, General Gage ordered the Massachusetts Assembly to meet in Salem, but sensing the growing opposition, he canceled the meeting. Ninety representatives showed up anyway. Since Gage and his councilors were absent, they concluded that Gage had abdicated his authority and they declared themselves the effective (if not strictly legal) government of Massachusetts, naming themselves the Provincial Congress and electing John Hancock as its president.

Both the provincials and General Gage could see that they were drawing perilously close to war. If the Massachusetts militias mobilized, Gage knew they would overwhelm his occupying force of a few thousand soldiers, so he attempted to cut off their supply of gunpowder. On September 1, he sent troops to move more than two hundred barrels of powder from Quarry Hill (in what is now Somerville) to Castle William, a British fort on an island in Boston Harbor. The following day, four thousand or more club-wielding protestors marched in Cambridge to protest the removal of the powder.

Meanwhile in Worcester, a group calling itself the American Political Society had set itself up as an independent governing body and directed towns to form companies of minutemen, the elite fighting force of the town militias. If Gage sent troops to enforce his control, the towns would deploy “properly armed and accoutered” militias to “protect and defend the place invaded.”2

The powder house at Quarry Hill (now Somerville, MA) where British troops seized over 200 barrels of gunpowder in 1774

| Public domain. Commons.wikimedia.orgBy the early months of 1775, the Provincial Congress had procured one thousand barrels of powder, five thousand muskets with bayonets, and “all kinds of warlike stores, sufficient for an army of fifteen thousand.”3 They arranged to have them hidden in attics, cellars, and barns in Worcester and Concord.

In March 1775, committees of the Provincial Congress directed Colonel James Barrett, commander of Concord’s minutemen, “to keep a suitable number of teams in constant readiness, by day and night.”4 Reverend William Emerson warned his Concord flock, “In all probability you will be called to real service . . . [There is] an approaching storm of war and bloodshed.”5 That same month, General Gage ordered two of his officers, Captain John Brown and Ensign Henry De Berniere, to disguise themselves as civilians and go to Concord to reconnoiter. They mapped the roads and observed with some alarm that it was “an armed camp, with sentries posted at its approaches, and vast quantities of munitions on hand.”6

The Provincial Congress resolved on April 8 that it was “necessary for this colony to make preparations for their security and defence, by raising and establishing an army,”7 and published a booklet called Rules and Regulations for the Massachusetts Army in flagrant defiance of English rule.

General Gage studied the intelligence gathered by his spies, Brown and De Berniere, and on the night of April 18, he sent troops to Concord to disarm the provincials. He badly underestimated their readiness and their resolve, as he would soon learn.

NOTES

1 William Cobbett and T C. Hansard. The Parliamentary History of England from the Earliest Period to the Year 1803. London, Printed by T.C. Hansard [etc.] 1806-20.

2 William Lincoln, ed. The Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775. Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State, 1838

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 William Emerson; Amelia Forbes Emerson. Diaries and letters of William Emerson, 1743-1776. Privately printed, 1972

6 David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994

7 Lincoln, op. cit