With the death of King George II on October 25, 1760, his 22-year-old grandson George III became the King of Great Britain and Ireland. Reports of the ascension of the new monarch reached the American colonies in early January 1761, and the first colonists to hear the news were the people of Massachusetts. The rise of the man who would become the last king of America was met with great fanfare and joy.

Boston, in particular, reacted to the new king with much celebration. As the proclamation was read aloud to the city, announcing Boston’s “faith and constant obedience” to George, the crowd shouted “Huzzah!” while militiamen fired three volleys and cannon boomed from Fort William in Boston Harbor. As night fell almost every window was illuminated by a candle in honor of the king. One Bostonian commented on the city’s excitement: “I don’t know of one single man but would risk his life and property to serve King George the Third.” One of the city’s newspapers, The Boson News-Letter, published a poem in the new king’s honor. It read, in part:

“Hail! Princely Youth! May guardian

powers defend

Thee, Britain’s safety; and to distant times

Transmit the honours of thy lengthen’d sway!”

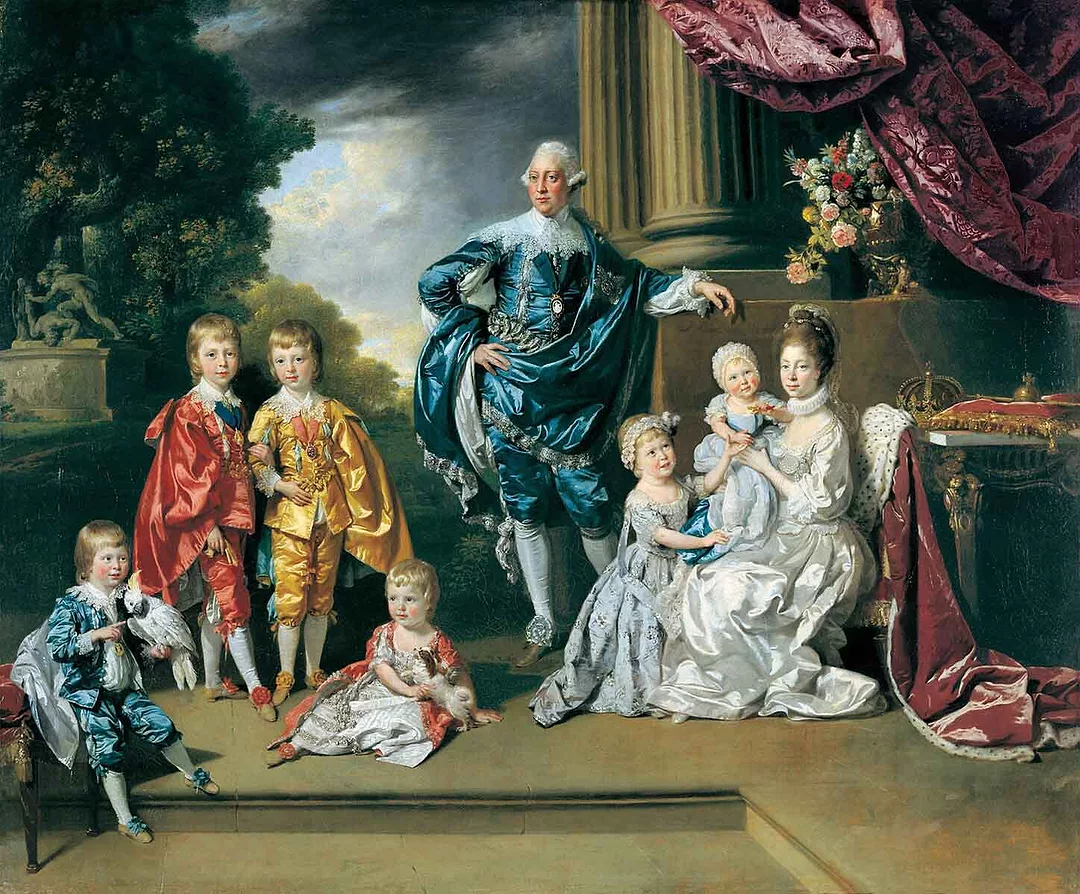

Portrait of George III. By Allan Ramsay; 1770.

Although he was a member of the ruling House of Hanover, George III was different from the two previous monarchs, George I (his great-grandfather) and George II (his grandfather). They had been born in Germany, but George III was the first Hanoverian monarch born in England. George III spoke English, and not German, as his first language. He immediately set out to distinguish himself from his predecessors, writing, “Born and raised in this country, I glory in the name of Briton.”

From the start of his reign the new king’s economic lifestyle and plain dress endeared him to the public. Described as “cultured, dutiful and intelligent” he was an avid reader and book collector and was deeply engaged in the social, economic, and political issues of the day; his personal library had over 65,000 books. He loved science, the arts, architecture, and especially agriculture; nicknamed “Farmer George” he grew wheat, barley, and turnips on his estates. He practiced crop rotation and pasture management, often walking his farming fields and tilling the soil himself. He was the first European king to study natural sciences, including astronomy, and in 1768 he had an observatory built just outside of London to observe the transit of the planet Venus across the face of the sun.

Another thing that set George III apart from previous monarchs was his marriage. In an era when royalty married to acquire wealth or land, George accepted an arranged marriage to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz because he loved her. He placed high value on personal and religious virtue and was notably faithful to his wife. They would have a happy and successful marriage, producing 15 children, 13 of whom lived to adulthood.

Today, George III is most often remembered as the “Mad King” for the periods of prolonged mental and physical illness that plagued the later years of his reign. Among the more alarming effects of the king’s illness were periods of mania; at their mildest he experienced “a desire of talking that he was unable to control,” and he would sometimes talk for hours until he was hoarse and foaming at the mouth. Sometimes he was uncontrollably violent towards his staff and even Queen Charlotte. These episodes were generally kept quiet, and period accounts differed over the cause of his illness. From this limited record, historians have proposed many possible diagnoses for the king including arsenic poisoning, porphyria and, most recently, bi-polar disorder.

Pulling Down the Statue of King George III at Bowling Green, N.Y. July 9, 1776. By William Walcutt; 1857.

George came to power in the midst of yet another struggle between England and France for world domination. The conflict spilled over to North America, where the so-called French and Indian War would ultimately decide which nation would control the continent. After seven years the French were defeated, but the war left Great Britain virtually bankrupt, with the country’s national debt nearly doubled. Starting in 1764, Parliament, with the support of George III, began to impose new taxes on the 13 American colonies in order to raise revenue to pay off the war debts. The colonists found this taxation unfair and insulting; this led to widespread riots, protests, and boycotts, with Boston’s “Sons of Liberty” leading the charge.

However, Boston’s rebels were quick to point out that, while they were angered at Parliament’s “unwarrantable encroachments and usurpations,” they still considered themselves loyal subjects of George III. One farmer even drove two oxen into Boston bearing a flag that read “King George Forever! Liberty and Property and NO STAMPS!”

Boston’s attitude towards the king would begin to sour in 1769 after George sent some 2,000 British soldiers to the city to quiet the growing unrest, and tension between the Redcoats and Bostonians reached a violent crescendo with the Boston Massacre in March 1770. After the bloodshed, the Sons of Liberty waged a propaganda campaign to stir up even more anti-British sentiment. Throughout the American colonies, talk of rebellion - and possibly even independence from Great Britain - began to spread.

After the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, the king had had enough of Boston’s rebels, and he acted swiftly. His Coercive Acts of 1774 closed Boston Harbor until the destroyed tea was paid for. He also ended the Massachusetts Constitution and restricted town meetings. And 4,000 more Redcoats arrived in Boston to ensure order. Massachusetts was now under direct control of Great Britain. In response to these “Intolerable Acts” Bostonians now took more extreme measures in their protest against British rule and the king. For all intents and purposes, they were under martial law, and Massachusetts citizens saw the Acts as a direct violation of their rights. In October 1774 delegates met in Concord and formed the Provincial Congress. With John Hancock elected as its president, this extralegal body became the de facto government of the colony, and Massachusetts militias began to prepare for bloodshed.

The American Revolution commenced with the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, and Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. In August, George officially declared the American colonies to be in a state of “open and avowed rebellion,” and he urged Parliament to quickly bring order to the colonies. But he didn’t sit idly by as his forces waged war thousands of miles away. He took an active role and studied military manuals, visited army encampments, and used maps and charts to follow the military campaigns in North America. He even kept detailed notes on financing the war, including such minutiae as the number of blankets the armies in North America needed.

All allegiance toward the king ended with the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. While many in the colonies remained loyal to the Crown, one third of the population supported the revolution and considered George a tyrant. And once independence was declared there was no turning back for the 13 colonies. In the Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson explicitly blamed George for the wrongs that led to revolution, while Parliament, the body that actually passed the legislation that so angered the colonists, was not mentioned at all.

A cartoon from 1775 shows George III and the Speaker for The House of Lords in an open chaise drawn by two horses labeled “Obstinacy” and “Pride,” about to lead Britain into the abyss of war with the American colonies.

John Adams was not pleased with this “scolding” of the king, later writing that he “never believed George to be a tyrant.” Still, the die was cast: King Street in Boston became State Street, King’s College became Columbia, and effigies of George were hanged and burned throughout the colonies. A giant equestrian statue of the king in Manhattan was pulled down by a mob and cut up, with the pieces being melted down to make musket balls for the Continental Army.

But was George III really the tyrant he was made out to be? Calling the rebellious Americans “treacherous” and “ungrateful” he wanted them brought under control and he willingly sent the men and material to do so. By 1779 some 60,000 British and German troops were in North America to put down the rebellion. However, the king never condoned or encouraged the type of scorched-earth campaign that could have ended the war quickly. As British historian Andrew Roberts noted, “It was partly because George was not a tyrant…that he lost the war against his so-called tyranny.”

After seven long years the war ended with the surrender of British troops at Yorktown in October 1781. The signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, ended hostilities and assured American independence. For his part, King George was distraught at the loss of his colonies; he even considered abdicating in 1781 after receiving the news of Yorktown. It would take him several years to finally come to terms with what he called “the Separation.”

In 1785, John Adams was appointed the first United States Minister Plenipotentiary to Great Britain. On May 26 of that year, he presented his credentials to King George III at the Palace of St. James. He addressed his former monarch, saying, “I think myself more fortunate, than all my fellow Citizens, in having the distinguished Honour, to be the first to Stand in your Majesty’s Royal Presence, in a diplomatic Character.” With a noticeably choked voice, the king recognized the “extraordinary” circumstances of the two men’s meeting. He made clear to Adams that while he had been “the last to consent to the Separation” he would be “the first to meet the Friendship of the United States as an independent Power.”

All images public domain